We Called It Earlier: Outdated Levers, Modern Consequences

If you saw our post earlier this week, you’ll know we questioned the very measures the RBA uses to guide its decisions. And sure enough, the RBA left the cash rate unchanged at 3.60 per cent; because it’s still steering with instruments built for yesterday’s economy. The framework was forged in a long, stable era…

If you saw our post earlier this week, you’ll know we questioned the very measures the RBA uses to guide its decisions. And sure enough, the RBA left the cash rate unchanged at 3.60 per cent; because it’s still steering with instruments built for yesterday’s economy. The framework was forged in a long, stable era (read more about this in last week’s blog); today’s inflation is being driven by structural supply failures that the cash rate can’t fix.

This isn’t classic overheating; it’s policy-induced scarcity.

Energy: A shift toward renewables without replacement capacity has left the market short; price spikes and lumpy supply responses are features, not bugs. Even the RBA’s own liaison noted delayed critical minerals projects and whipsaw investment conditions.

Housing: Planning drag, construction constraints and credit settings bite on the supply side. Lifting or lowering the policy rate doesn’t build homes. (The Governor herself has said monetary policy can’t “fix” house prices born of supply.)

You can’t solve supply shocks with demand brakes. Keep doing that and you get the worst mix: stubborn prices, weak growth, and rising household stress.

So where is the opportunity?

All risk comes from a lack of knowledge. To understand how to best leverage the opportunity, we need to understand why a ‘fix’ isn’t coming. It starts with a flawed economic system.

From Real Provisioning to Abstract Levers: How Economic Focus Drifted

To understand why modern monetary policy feels disconnected from lived reality, it helps to trace how economics itself evolved. Up until the mid-20th century, most policy and theory still revolved around real provisioning. This means feeding, housing, and employing populations. Even through the early industrial age, governments saw economic health in tangible terms: land productivity, food security, and public works that lifted living standards. Central to this was shelter – housing.

After World War II, a new institutional economics took hold. The creation of the national accounts system (UN SNA 1953), the Bretton Woods order, and Australia’s 1945 White Paper on Full Employment shifted the economic compass from real production toward aggregate management: GDP growth, capital formation, and balance-of-payments stability. The intent was sound: build tools to stabilise modern economies. But the effect was to abstract policy away from land, housing, and supply foundations, embedding a reliance on fiscal and monetary fine-tuning instead of direct provisioning.

Let’s just stop to understand that for a second. This means that in the 1950s, there was an intentional shift from economic policy being focused on ensuring you have a home and food, to governments having money. When policy is guided by the wrong measures, even the best compass leads you astray.

By the early 1990s, the final pivot arrived with inflation targeting, a narrow 2–3 per cent focus that cemented price stability as the overriding goal. While the framework proved useful in taming demand-driven inflation, it has struggled with structural, supply-side shocks such as energy transitions and housing shortages. Australia’s system, though officially “flexible,” still defaults to demand suppression even when prices are driven by scarcity, not excess spending.

In this sense, today’s economic challenge is partly an intellectual inheritance. A discipline once centred on sustaining communities through tangible production has become one of managing aggregates through interest rates. Rebalancing the system will require more than technical tweaks; it means restoring a connection between monetary settings, real supply capacity, and the physical economy of housing, energy, and productivity.

Back to today’s RBA:

The structural problem isn’t only economic, it’s institutional

Noting that monetary policy hasn’t exactly gone to plan since its inception in the early 1990s, Australia started to remodel the RBA after the 2023 independent review. Unfortunately, the changes are mid-stream and contested. A split between a Monetary Policy Board and a Governance Board, fewer but longer meetings, and more transparency are in train; debates continue over publishing votes and the government’s historic veto/override power.

- Board re-design & appointments: Canberra moved to shift existing externals onto the new rate-setting board to secure passage of reforms, prompting concerns about politicisation and credibility from some heavy hitters.

- Government override: The Treasurer has signalled limiting any veto to “emergencies,” but clarity in statute and practice still matters for independence.

- Dual boards: Supporters say clearer roles, critics warn duplication risks diluting accountability. Either way, none of this builds a single house or adds a watt of electricity capacity.

Bottom line: Governance tweaks are welcome but insufficient. Australia needs a joined-up monetary-fiscal-supply strategy, with housing and productivity at the core, not footnotes.

The dual-mandate tension (and why some argue for a “clean” mandate)

Legally, the RBA now speaks plainly about its dual mandate, price stability and full employment, under the umbrella purpose of promoting Australians’ prosperity. The trade-off is real: when inflation is pushed by supply shocks, tightening to hit CPI can lift unemployment. Even pro-dual-mandate economists acknowledge that the priority often falls on inflation in practice.

This is why some critics want a single, “clean” price-stability mandate (with jobs left to fiscal policy and labour-market design) to avoid blurred responsibility and policy buck-passing when employment deteriorates. Others counter that a flexible dual mandate keeps the bank honest about the real economy.

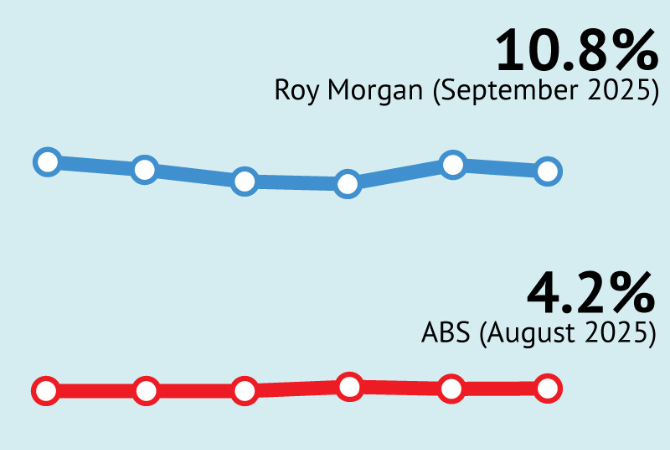

The unemployment metric problem (and better lenses)

If you’re going to target “full employment,” you need measures that reflect work reality.

- One-hour rule: By international convention (ILO-aligned), the ABS counts anyone who worked ≥1 hour in the reference week as employed. It’s standard, but it flatters the headline jobless rate when underemployment is high.

- Underemployment & underutilisation: Think part-timers chasing hours or multiple job-holders patching income. Alternative gauges (e.g., Roy Morgan’s series) consistently show higher “real” unemployment/under-employment than the ABS headline. Methodologies differ, but the gap is exactly the point: the headline rate understates slack.

Roy Morgan+2Roy Morgan+2

What to watch instead: Underemployment, underutilisation, hours worked, job vacancies per unemployed person, and multiple-job-holding. If those are moving the wrong way while CPI is driven by supply, the dual-mandate conflict is flashing bright red.

In summary, the economic system lost its focus on people and is now globally entrenched without any inclination to change. The RBA started its current mandate during the 30 most peaceful years of human civilisation, a time we won’t return to, and it failed us. The entire premise of the cause being the cure means nothing will change in a hurry to build the homes needed, forcing a protracted cycle of increasing house prices and rents.

Our stance (and what investors can do)

Australia isn’t just short on supply, it’s short on strategy. Until policy pivots to coordinated supply-side fixes (planning, approvals, labour, materials, firming in energy) alongside a clearer monetary framework, the cash rate will keep doing too much of the wrong job.

That’s why we focus on evidence, timing and location: buying into durable supply–demand imbalances with real drivers (infrastructure catchments, resilient employment hubs, genuine scarcity) rather than macro noise.

Strategy beats headlines.

When we design an outcome for our clients, we take all this into account and so much more. Your success is individual, and so should your strategy be. Where Governments come up short, we understand the failures, how we got here, what it means and how best to leverage the current position and the future implications, in light of the same for you personally.

Strategy beats acquisition alone.